25 years later: Rwanda learns to teach genocide, not only remember

Serge Rwigamba speaks to visitors at the Kigali Genocide Memorial.

Vivian Irabiz, 22, is one of more than 60% of the population born after the genocide.

D’Artagnan Habintwal, a guide at the Kigali Genocide Memorial, says young people in Rwanda dream of a better place.

By Vimvam Tong and Rachel Yeo

500

Serge Rwigamba was 13 when his parents were killed in the 1994 genocide against the Tutsis and moderate Hutus that left more than a million dead in Rwanda. He grew up an orphan supported by government assistance.

Serge Rwigamba was 13 when his parents were killed in the 1994 genocide against the Tutsis and moderate Hutus that left more than a million dead in Rwanda. He grew up an orphan supported by government assistance.

Now, Mr. Rwigamba, 38, works as a visitor engagement officer at the Kigali Genocide Memorial, where 250,000 victims, including his parents, are buried.

“I still have to face a lot other consequences left by the genocide: trauma, troubles in personality, educational challenges,” Mr. Rwigamba, who suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder, said.

Around 35% of Rwandan genocide survivors are estimated to suffer from trauma and other mental health problems, according to a study by Rwanda Mental Health.

But though many like Mr. Rwigamba continue to confront the horrors of genocide 25 years later, most of Rwanda’s more than 12 million people are too young to have lived through or remember the genocide.

In the 2012 census, 62% of the population was under 25, most of them children of survivors, and the current median age is 19.6, based on UN data.

On April 7, the country entered 100 days of mourning to commemorate the genocide that happened 25 years ago.

But the real challenge the country faces is not how to remember the past, but how to teach it.

Vivian Irabizi, 22, a student interning at the local English paper The New Times, met her father for the first time when she was 14. After the genocide, her parents fled to Congo and were separated, each thinking the other had died.

Vivian Irabizi, 22, a student interning at the local English paper The New Times, met her father for the first time when she was 14. After the genocide, her parents fled to Congo and were separated, each thinking the other had died.

Her mother came back to Rwanda and gave birth to her, raising her as a single parent. Now, even though her family has been reunited, she still carries emotional pain over the lost years.

“Today I have a father. I struggled to call him “father”. I used to call “fa……” and then would burst into tears,” she said.

After the genocide, Rwandans no longer classify themselves as Tutsi or Hutu, they are simply known as Rwandans. Ms. Irabizi said that the young generation should be active to learn and unite themselves as “all Rwandans”.

Educating the young about a tragedy that they did not experience is challenging, many older survivors say.

D’Artagnan Habintwali, who was 5 during the genocide and is now a guide at the Kigali Genocide Memorial, said that it can be difficult for teachers in the classroom, even though programmes are in place to help educators.

D’Artagnan Habintwali, who was 5 during the genocide and is now a guide at the Kigali Genocide Memorial, said that it can be difficult for teachers in the classroom, even though programmes are in place to help educators.

“Sometimes the teachers were not comfortable and they would skip the chapter of the genocide or will only summarise it,” Mr. Habintwali said.

“But after trainings and workshops, teachers have opened up and talked about their experiences. In Rwanda, there is a saying, ‘if you have a sickness, its better to talk about it than hide it’.”

Adolphe Nimbona, a 30-year-old tour guide and driver, said it is difficult to teach the genocide because some of the students’ parents might have participated.

Mr. Nimbona said he and his mother survived with help from their Hutu friend.

Without “hope, safety, food, way to hide”, Mr. Nimbona recalled that “about 15 soldiers came in to my home and started to shoot the back of some of our group mates with guns.”

“There is no hope. Everything is destroyed. The house was broken down. No people we can meet again, my friends, uncles, cousins,” he said.

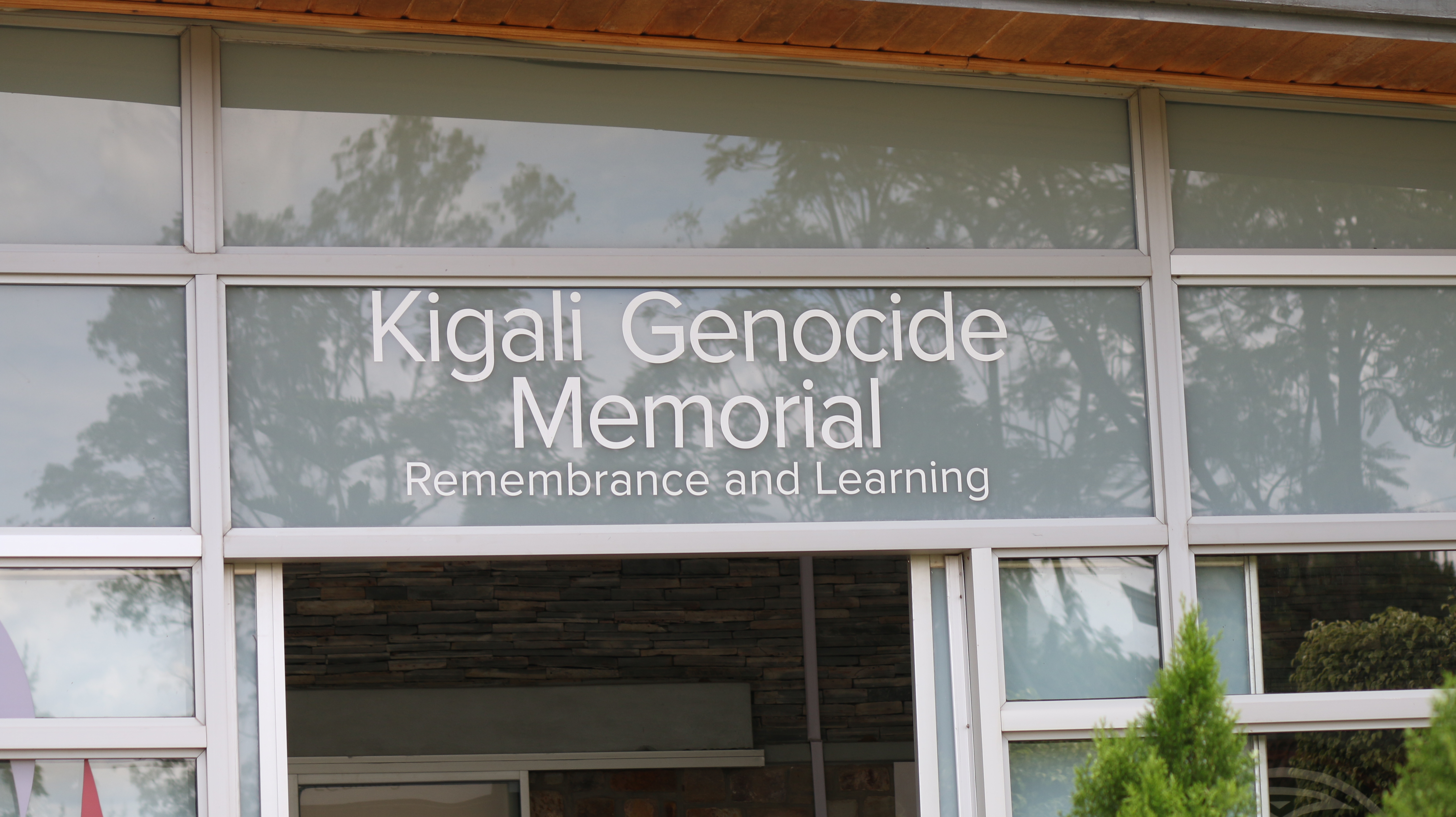

The Kigali Genocide Memorial is one of six in the city with many smaller memorials scattered around the country. It is also the largest memorial and calls itself a place of remembering and learning.

Mr. Nimbona said he will help young people know the truth of the genocide, encouraging people to face up to the past and then move forward.

“People bring the devil inside to make something happen, to teach people about forgiving. You can’t make anger every time,” he said.

Mr. Rwigamba said he also chooses to forgive.

“It’s hard for some people to face the prejudices after the genocide. The perpetrators live in guilt. They were guilty about what their parents did,” he said.

He tells visitors in the memorial that moving forward needs everyone’s understanding. “Because the world grows up as a union. Prejudice does not help anyone,” he said.

Mr. Habintwali said that changing mindsets and promoting harmony will help the next generation to learn from past mistakes.

“In Rwanda, the genocide happened because our grandfathers dreamed of the genocide. If today we dream of a better place, a better Rwanda, then our children will be in a better place in a good country,” he said.