Rwanda fights for the mountain gorillas

Ex-poacher village and Dian Fossey’s research centre continue conservation work

By Anna Kam and Phoebe Lai

Award-winning biopic Gorillas in the Mist, released in 1988, features primatologist Dian Fossey’s fight to protect mountain gorillas from poachers. It was the first film to bring mountain gorillas and the dangers they face in their natural habitats in East Africa to the attention of the world.

“Give my gorillas the protection they are entitled to,” said actress Sigourney Weaver, who played Ms. Fossey in the film, in an iconic scene where she helps a gorilla in her lap drink water.

Thirty years after Gorillas in the Mist, once again gorillas captured the world’s attention when a photo of two gorillas posing for a selfie with African ranger Mathieu Shamavu went viral last month. The two animals hilariously mimic human postures while looking directly into the camera.

The photo was taken at a gorilla orphanage in Virunga National Park in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where the gorillas are being raised after poachers killed their parents.

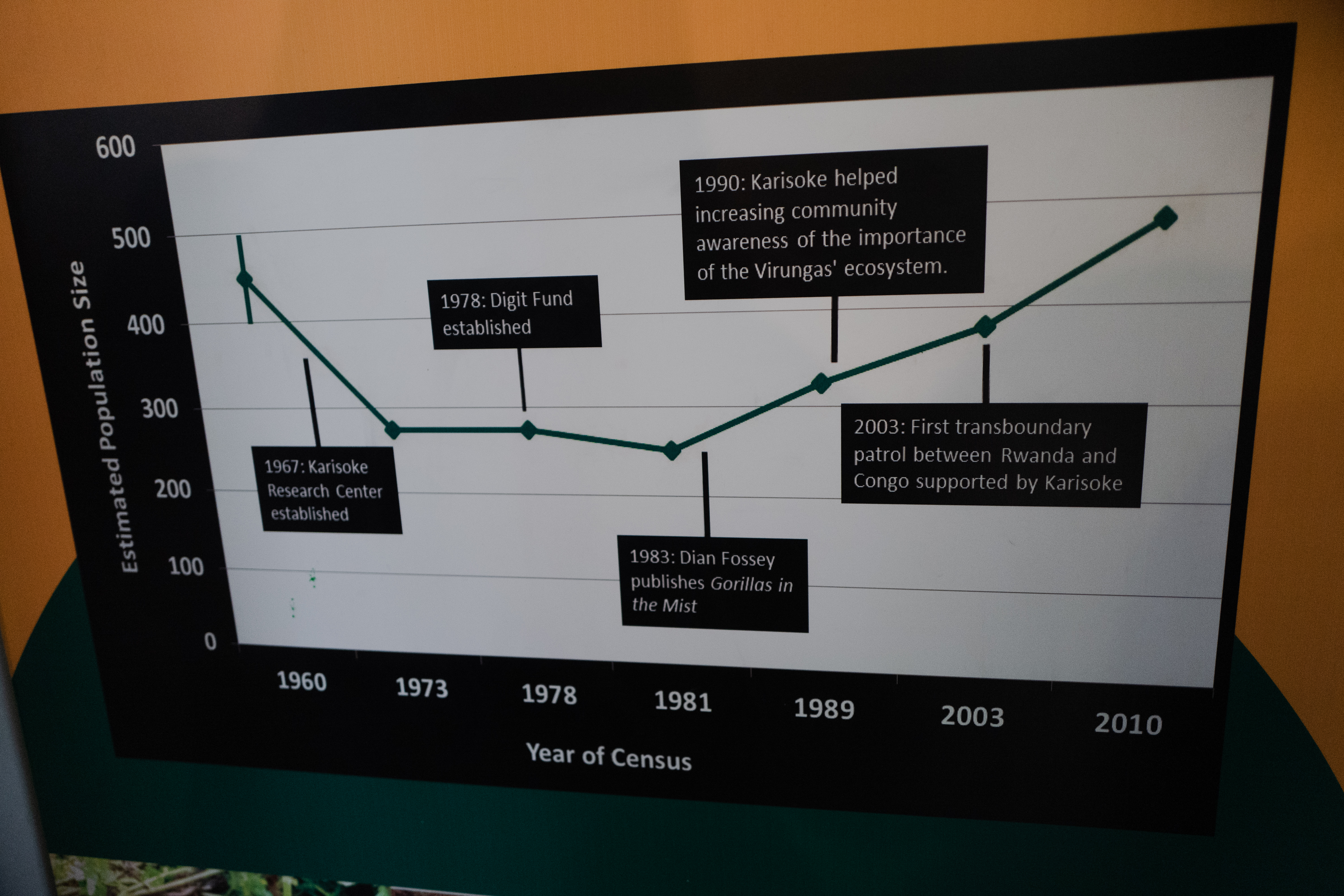

While poaching continues to be a problem in violence-plagued Congo, neighbouring Rwanda’s current gorilla population is the highest since the 1960s.

The fight against poaching, the regulation of tourism and scientific research have all contributed to conservation in the country that is building on a legacy left by Ms. Fossey, who was murdered in Rwanda in 1985.

The mountain gorilla, commonly known as the silverback and a subspecies of the eastern gorilla, is found in only two places on earth, high up in the bamboo forests of the Virunga mountains that span the borders of Rwanda, Uganda and the DRC and in the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in Uganda.

After facing near extinction, mountain gorillas were last year moved from “critically endangered” to “endangered,” with a population estimated to be a little over 1,000.

To see the gorillas in Rwanda, guided tracking tours can be booked through the Volcanos National Park, which limits visitors to 96 per day, spread across 12 gorillas families. In 2017, the govenrment raised the price of the permit to US$1,500 (HK$ 11,759).

At the Gorilla Guardians’ Village, a cultural village founded near the Volcanos National Park in Rwanda by former park warden Edwin Sabuhoro in 2006, former and would-be poachers teach visitors about traditional village life, music and dance as an alternative source of income.

Mr. Sabuhoro, who initially worked undercover to catch poachers, heard devastating stories of poverty from the people he arrested and decided to help. He first used up his savings to rent land for the poachers to farm. Then he set up Rwanda Eco-tours and the cultural village to employ ex-poachers and give them an incentive to conserve wildlife.

Some poachers kill gorillas for meat, but others accidently injure or kill gorillas while trying to catch antelope, wild pigs or buffalo with traps and snares, according to The International Gorilla Conservation Programme. Sometimes baby gorillas are sold to zoos.

“We didn’t eat the gorillas. When the gorillas were caught in our traps, we cut it and let it go away,” said Twagirimana Innocent, the son of an ex-poacher, who used to accompany his father to hunt animals when he was younger and now works as a tour guide in the village.

“They stole babies and sold them to poachers from Uganda and other neighbouring countries, each for US $2,000,” said Mr. Innocent. “They kept them in farms as pets; some did sell them to zoos.”

Last June, a leaked letter showing the attempted sale of critically endangered wildlife, including a dozen mountain gorillas, from the Institute in Congo for the Conservation of Nature, to two zoos in eastern China. The document sparked outrage among wildlife protection and civil society groups such as Born Free and Conserv Congo. It eventually led to an online petition to prevent the export of the animals, which has been signed by over 9,000 people.

Barora Leonidas, around 80 years old, who was a poacher for at least 30 years, lost two of his front teeth when he was poaching as a boy because he was kicked in the face by an buffalo, he said. He now works in the village as an entertainer.

“When choosing being hungry and poaching a baby gorilla, of course the locals will choose to sell the baby gorilla,” he said.

Infant orphan gorillas are especially vulnerable to stress and malnutrition in captivity, according to the Gorilla Rehabilitation and Conservation Education center, an NGO in Kenya.

At the Karisoke Research Center, founded by Ms. Fossey near Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park, Laban Kayitete , an intern biologist, said gorillas can be harmed or even killed, even if they are only a “bycatch”.

Veronica Vecellio, the center’s Gorilla Program Senior Advisor and Regional Public Relations Director, said in an email there are at most two cases of monitored gorillas being mistakenly captured in snares from poachers each year. In the past five years, there are a total of five gorillas caught in snares.

Most monitored gorillas caught will survive because researchers from the centre will interven with veterinarians to remove the snare, but it is possible that a gorilla would not survive the ordeal if rescue comes late, she said.

“If we don’t see them and the rope gets too tight they may die,” Ms. Vecellio said.

In July 2012, female juvenile gorilla, Ngwino, in Rwanda, did not survive her infected injury when the team of gorilla doctors finally removed the rope snare that had been on her left ankle five days after the incident. According to the online report from gorilla doctors, the rope snare has caused severe damage to the tissue of Ngwino’s left foot.

Ms. Vecellio said, they were unable to remove the snare immediately at scene because the group was in a deep ravine.

Various exhibits that show the snares made by poachers and lists of initiatives to stop poachers from catching gorillas mistakenly are on display at the Research Center.

A mountain gorilla’s genes are 98% similar to human DNA and as they live near cities, they face the danger of disease, human-wildlife conflict and poaching. Visitors who have recently been sick are not allowed to visit gorillas.

Ideally, conservationists “work with the community leaving near the park to provide alternatives of the use of natural resources and education to teach the importance to protect the environment,” Ms. Vecellio said.

Mountain gorilla guide Francois Bigirimana imitates a gorilla at the visitor centre. Mr. Bigirimana is the most experienced guide at the park worked with Dian Fossey on her research

Barora Leonidas was a poacher for 30 years and now works at the Gorilla Guardians cultural village. He lost his front teeth when he kicked in the face by an antelope when poaching, he said.